Terminal velocity

In fluid dynamics an object is moving at its terminal velocity if its speed is constant due to the restraining force exerted by the air, water or other fluid through which it is moving.

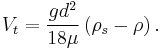

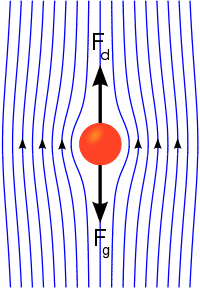

A free-falling object achieves its terminal velocity when the downward force of gravity (Fg) equals the upward force of drag (Fd). This causes the net force on the object to be zero, resulting in an acceleration of zero.[1]

As the object accelerates (usually downwards due to gravity), the drag force acting on the object increases, causing the acceleration to decrease. At a particular speed, the drag force produced will equal the object's weight  . At this point the object ceases to accelerate altogether and continues falling at a constant speed called terminal velocity (also called settling velocity). Terminal velocity varies directly with the ratio of weight to drag. More drag means a lower terminal velocity, while increased weight means a higher terminal velocity. An object moving downward with greater than terminal velocity (for example because it was affected by a downward force or it fell from a thinner part of the atmosphere or it changed shape) will slow until it reaches terminal velocity.

. At this point the object ceases to accelerate altogether and continues falling at a constant speed called terminal velocity (also called settling velocity). Terminal velocity varies directly with the ratio of weight to drag. More drag means a lower terminal velocity, while increased weight means a higher terminal velocity. An object moving downward with greater than terminal velocity (for example because it was affected by a downward force or it fell from a thinner part of the atmosphere or it changed shape) will slow until it reaches terminal velocity.

Contents |

Examples

Based on wind resistance, for example, the terminal velocity of a skydiver in a free-fall position with a semi-closed parachute is about 195 km/h (120 mph or 55 m/s).[2] This velocity is the asymptotic limiting value of the acceleration process, because the effective forces on the body balance each other more and more closely as the terminal velocity is approached. In this example, a speed of 50% of terminal velocity is reached after only about 3 seconds, while it takes 8 seconds to reach 90%, 15 seconds to reach 99% and so on. Higher speeds can be attained if the skydiver pulls in his or her limbs (see also freeflying). In this case, the terminal velocity increases to about 320 km/h (200 mph or 90 m/s),[2] which is also the terminal velocity of the peregrine falcon diving down on its prey.[3] And the same terminal velocity is reached for a typical .30-06 bullet travelling in the downward vertical direction — when it is returning to earth having been fired upwards, or perhaps just dropped from a tower — according to a 1920 U.S. Army Ordnance study.[4]

Competition speed skydivers fly in the head down position reach even higher speeds. The current world record is 614 mph (988 km/h) by Joseph Kittinger, set at high altitude where the lesser density of the atmosphere decreased drag.[2]

An object falling toward the surface of the Earth will fall 9.81 meters (or 32.18 feet) per second faster every second (an acceleration of 9.81 m/s² or 32.18 ft/s²). The reason an object reaches a terminal velocity is that the drag force resisting motion is approximately proportional to the square of its speed. At low speeds, the drag is much less than the gravitational force and so the object accelerates. As it accelerates, the drag increases, until it equals the weight. Drag also depends on the projected area. This is why things with a large projected area, such as parachutes, have a lower terminal velocity than small objects such as bullets.

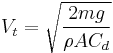

Mathematically, terminal velocity — without considering the buoyancy effects — is given by

where

= terminal velocity,

= terminal velocity, = mass of the falling object,

= mass of the falling object, = acceleration due to gravity,

= acceleration due to gravity, = drag coefficient,

= drag coefficient, = density of the fluid through which the object is falling, and

= density of the fluid through which the object is falling, and = projected area of the object.

= projected area of the object.

Mathematically, an object approaches its terminal velocity asymptotically.

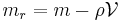

Buoyancy effects, due to the upward force on the object by the surrounding fluid, can be taken into account using Archimedes' principle: the mass  has to be reduced by the displaced fluid mass

has to be reduced by the displaced fluid mass  , with

, with  the volume of the object. So instead of

the volume of the object. So instead of  use the reduced mass

use the reduced mass  in this and subsequent formulas.

in this and subsequent formulas.

On Earth, the terminal velocity of an object changes due to the properties of the fluid, the mass of the object and its projected cross-sectional surface area.

Air density increases with decreasing altitude, ca. 1% per 80 metres (262 ft) (see barometric formula). For objects falling through the atmosphere, for every 160 metres (525 ft) of falling, the terminal velocity decreases 1%. After reaching the local terminal velocity, while continuing the fall, speed decreases to change with the local terminal velocity.

Derivation for terminal velocity

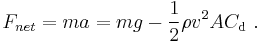

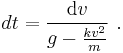

Mathematically, defining down to be positive, the net force acting on an object falling near the surface of Earth is (according to the drag equation):

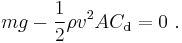

At equilibrium, the net force is zero (F = 0);

Solving for v yields

| Derivation of the solution for the velocity v as a function of time t |

|---|

|

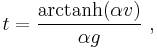

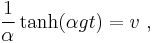

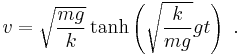

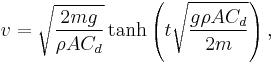

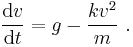

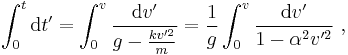

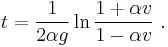

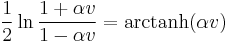

The drag equation is A more practical form of this equation can be obtained by making the substitution k = 1⁄2ρACd. Dividing both sides by m gives The equation can be re-arranged into Taking the integral of both sides yields where α = ( k⁄mg )1⁄2. After integration, this becomes or in simpler a form The inverse hyperbolic tangent is defined as:

So the solution of the integral is or alternatively, with tanh the hyperbolic tangent function. Assuming that g is positive (which it was defined to be), and substituting α back in, the velocity v becomes Next, after k = 1⁄2ρACd has been substituted, the velocity v is in the desired form: As time tends to infinity ( t → ∞ ), the hyperbolic tangent tends to 1, resulting in the terminal velocity |

Terminal velocity in the presence of buoyancy force

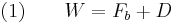

When the buoyancy effects are taken into account, an object falling through a fluid under its own weight can reach a terminal velocity (settling velocity) if the net force acting on the object becomes zero. When the terminal velocity is reached the weight of the object is exactly balanced by the upward buoyancy force and drag force. That is

where

= weight of the object,

= weight of the object, = buoyancy force acting on the object, and

= buoyancy force acting on the object, and = drag force acting on the object.

= drag force acting on the object.

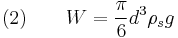

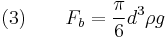

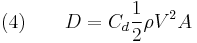

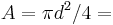

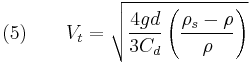

If the falling object is spherical in shape, the expression for the three forces are given below:

where

diameter of the spherical object

diameter of the spherical object gravitational acceleration,

gravitational acceleration, density of the fluid,

density of the fluid, density of the object,

density of the object, projected area of the sphere,

projected area of the sphere, drag coefficient, and

drag coefficient, and characteristic velocity (taken as terminal velocity,

characteristic velocity (taken as terminal velocity,  ).

).

Substitution of equations (2–4) in equation (1) and solving for terminal velocity,  to yield the following expression

to yield the following expression

.

.

Terminal velocity in creeping flow

For very slow motion of the fluid, the inertia forces of the fluid are negligible (assumption of massless fluid) in comparison to other forces. Such flows are called creeping flows and the condition to be satisfied for the flow to be creeping flows is the Reynolds number,  . The equation of motion for creeping flow (simplified Navier-Stokes equation) is given by

. The equation of motion for creeping flow (simplified Navier-Stokes equation) is given by

where

= velocity vector field

= velocity vector field = pressure field

= pressure field = fluid viscosity

= fluid viscosity

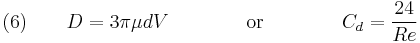

The analytical solution for the creeping flow around a sphere was first given by Stokes in 1851. From Stokes' solution, the drag force acting on the sphere can be obtained as

where the Reynold's number,  . The expression for the drag force given by equation (6) is called Stokes law.

. The expression for the drag force given by equation (6) is called Stokes law.

When the value of  is substituted in the equation (5), we obtain the expression for terminal velocity of a spherical object moving under creeping flow conditions:

is substituted in the equation (5), we obtain the expression for terminal velocity of a spherical object moving under creeping flow conditions:

Applications

The creeping flow results can be applied in order to study the settling of sediment particles near the ocean bottom and the fall of moisture drops in the atmosphere. The principle is also applied in the falling sphere viscometer, an experimental device used to measure the viscosity of high viscous fluids.

See also

- Stokes' law

- Free fall

References

- ↑ "Terminal Velocity". NASA Glenn Research Center. http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/K-12/airplane/termv.html. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Huang, Jian (1999). "Speed of a Skydiver (Terminal Velocity)". The Physics Factbook. Glenn Elert, Midwood High School, Brooklyn College. http://hypertextbook.com/facts/JianHuang.shtml.

- ↑ "All About the Peregrine Falcon". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007-12-20. http://www.fws.gov/endangered/recovery/peregrine/QandA.html.

- ↑ The Ballistician (March 2001). "Bullets in the Sky". W. Square Enterprises, 9826 Sagedale, Houston,Texas 77089. http://www.loadammo.com/Topics/March01.htm.

External links

- Terminal Velocity - NASA site

![t-0={1 \over g}\left[{\ln(1+\alpha v^\prime) \over 2\alpha}-\frac{\ln(1-\alpha v^\prime)}{2\alpha}+C \right]_{v^\prime=0}^{v^\prime=v}={1 \over g} \left[{\ln \frac{1+\alpha v^\prime}{1-\alpha v^\prime} \over 2\alpha}+C \right]_{v^\prime=0}^{v^\prime=v},](/I/1cd9b603eedb0f7f5104da47cf1b88c9.png)

.

.